Into the Fire: Within, between, & beyond the lines

Pentecost 15C: Jeremiah 2:4-13, Psalm 81:10-16, Hebrews 13:1-8, 15-16, Luke 14:1, 7-14

Italicized taglines like the one found at the bottom of all of the “Into the Fire” posts typically go unread. That being the case, I want to describe the process of Midrash a bit here. Here is a link to a former mentor’s three-part post about Midrash, which I credit completely for what follows in this post. We'll look at the process and then try it out, after the jump.

Italicized taglines like the one found at the bottom of all of the “Into the Fire” posts typically go unread. That being the case, I want to describe the process of Midrash a bit here. Here is a link to a former mentor’s three-part post about Midrash, which I credit completely for what follows in this post. We'll look at the process and then try it out, after the jump.

My mother, who is a retired elementary school teacher, always says that while reading we should:

- Read within the lines: What is the author telling me?

- Read between the lines: What does the author want me to think about?

- Read beyond the lines: What is of value here? How will I be changed in thinking and living?

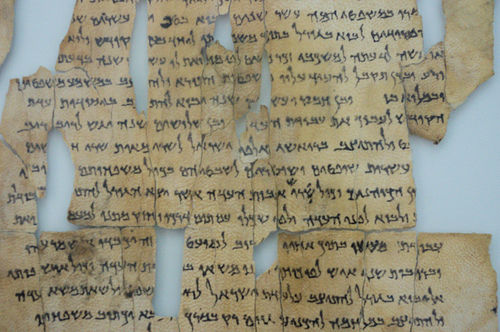

Ancient rabbis spoke of the Torah (that which is contained in the first five books of the Bible) as “black fire on white fire,” meaning that text (black fire) and the space around it (white fire) are to be read and studied in order to reach a fuller understanding of God’s instruction.

Apparently the wisdom of those ancient rabbis made it to my mother’s pedagogical sensibility—they’re essentially talking about the same thing. For a fuller understanding of any written thing, one must read the words, study the literary, cultural, and historical context, and attempt to make sense of lingual differences while engaging text on literal and allegorical levels.

One might even argue that God intended for us to bring our imaginations into studying scripture—if God hadn’t, the Torah would have included vowel marks or punctuation. Anyone who tells you a simply literal interpretation of scripture is possible hasn’t studied it enough to know any better.

So how do we do Midrash, an ancient Jewish method for Biblical study and interpretation?

There are four steps, which I’ve lifted directly from the blog post I mentioned earlier.

- P’shat (lit. Simple). Read the text for its simplest, most literal meaning. For example, if the Torah says God spoke to Moses through a burning bush, we are not allowed to say God spoke to Moses through an exploding cigar. It is also known as the grammatical level.

- Remez (lit. Hint). Rather than avoiding what appear to be contradictions or textual errors, or trying to explain them away, this step calls us seek them out as hints of deeper meaning. This is sometimes called the allegorical level.

- D’rash (lit. Investigation). In this step, we use our imaginations (and the imaginations of others) to explore all possible meanings and applications of the text. This is sometimes called the parabolic or homiletical level of Midrash.

- Sod (lit. Secret). Finally, we are called to open ourselves to the mysteries revealed to us through creative imagination of D’rash. This level of meaning is sometimes referred to as the mystical level.

Want to give it a try? Let’s take a look at Hebrews 13:15-16, a portion of one of the readings for this Sunday.

“Through [Jesus Christ], then, let us continually offer a sacrifice of praise to God, that is, the fruit of lips that confess his name. Do not neglect to do good and to share what you have, for such sacrifices are pleasing to God.”- P’shat (Simple): Pat, our unknown writer of the letter to the Hebrews, suggests that we offer our praise to God as a sacrifice—this praise is lip fruit that confess the name “Jesus Christ.” We know right away that the simple/literal translation does not make sense.

- Remez (Hint): Assuming Pat meant to say that our praise is both a fruit and a sacrifice, something is going on here. “Fruit” reminds us of abundance, while “sacrifice” conjures up images of Jacob and Isaac, or more practically, of giving something up of that which you’d rather not give. Fruit and sacrifice are connected, not necessarily opposed, and are leading us to the “meat” of this passage—perhaps with an apricot glaze?

Now comes the part of Midrash that is so much better done in dialogue—not only with you and the text, but you and other people!

- D’rash (Investigation): Considering that Pat wrote these sentences as part of other practical instructions to the Hebrews, some of the other advice might give us a better idea of what Pat means. “…Be content with what you have…” from 13:5 sticks out to me. Pat writes about possessions—wealth.

Then in our passage, Pat writes about sacrificing praise to God. Could it be that praise to God necessitates that we be giving up something we want? That doesn’t make God sound like someOne I’m much interested in seeking. This actually makes God sound like the same kind of Being that is the object of pagan worship—God enjoys this, so we give God this, and God is pleased, and maybe God will give us things.

But…but…no! Because…Jesus!

Our belief in God is a belief/hope that love reigns beyond any immediate desire for any kind of wealth. Perhaps Pat is pointing out to the Hebrews that if we truly believe that, we will sacrifice those fleeting desires for the sake of our relationship with the One who sustains us throughout the entirety of life. Paradoxically, maybe our sacrifice becomes more like abundance—not in the form of an open bar at some eternal hotel lounge in the clouds, but an abundance that we can know in this lifetime.

There. I’ve “midrashed” and provided one possible meaning of this piece of text, but it is far from the only one. The next step is more difficult to include in a blog, which is why I’ve left it out in my “Into the Fire” posts. “Sod” is the step that must be lived—discerned in your soul and within your daily activity.

Continue to use Midrash in your own reading of scripture; keep reading the blog, and see where the mysteries ___, ___, and ___ the lines take you.

- Sod (Secret):

The Rev. Curtis Farr is the assistant rector of St. James’s Episcopal Church. He blogs for St. James’s every Wednesday, offering reflections on the readings of scripture from the upcoming Sunday.

Into the Fire is a weekly contribution to the creative and imaginative process of interpreting the black and white fire of Scripture (the text and everything around the it). Using an adapted process of Midrash, the author includes historical/cultural information, personal anecdotes, and other theologians’ ruminations on selected passages from the upcoming Sunday’s lectionary readings. All are welcome to journey into the fire by using the comment sections on the blog itself, or on Facebook or Tumblr.