The Dismembered Body of Christ

This post first appeared on OnFaith Voices

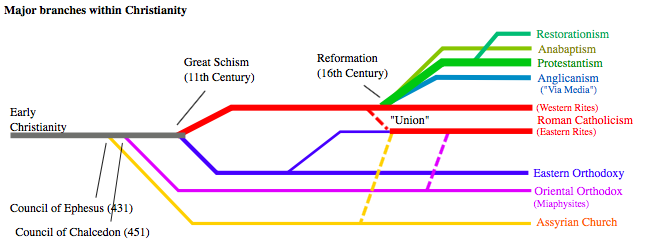

Looking from the outside in, Christianity’s degree of denominationalism seems competitive and at times non-productive…and perhaps even a bit absurd. Although most Christians have surely heard Saint Paul’s words that we are one body formed of many parts, we don’t often act like it—even within our denominations.

I would be a bit more optimistic about the diversity inherent in our denominationalism if the Episcopal “ear” ever coordinated with the Methodist “mouth” and Unitarian “uvula.” If we’re really one body, then why do we operate as if we’ve been dismembered?

In my experience, the churches that actually cross those denominational lines for this dialogue or that ecumenical service do so for assorted reasons, some of which are more self-serving than any of us would like to admit—focusing on ecumenism is not only good, it’s good PR. Stewards of any institution will do what is best for the preservation and enhancement of their institution, which can include the good and the bad (occasionally the ugly).

Take, for an over-simplified example, two or three small churches who are struggling to get by and spreading their leadership too thin; conceivably it would be in the best interest of all involved to consolidate and work on being a more effective and coherent group. Yet the strong (and understandable) emotional ties to a particular building, tradition, or name might (and often do) prevent consolidation from happening. And with too few people spread too thin to keep an institution operational, the real work of a faith community often gets neglected.

In this case, the institutional mindset may be limiting growth—not only growth in numbers, but also growth in capacity for the important business of loving to which I’d submit the body of Christ is called.

On the opposite end of the spectrum we have a different set of dilemmas relating to the institution. For example, a large church or seminary with an abundance of people and/or resources may have opportunities to buy a luxurious new rectory or to build an iconic chapel. One question such institutions must ask before spending such amounts of money is whether or not these things will help them improve their capacity for that important business of loving.

They should also ask themselves why they want to spend that money in those ways. While these kinds of expenditures are likely not motivated by a sense of denominational competition, they can begenerated from a sense that, “Our institution is paramount to the survival of the Gospel.”

And it’s not, I promise.

As wonderful as many of us believe our denominations, churches, seminaries, and other institutions are, the fact that we have so many is one sign that we have some golden calves in our midst.

This thought is hardly revolutionary, yet because our idolatry of institutions is typically something we implicitly accept or utterly ignore, we need to be dedicated to both talk about it and perhaps move from complacency to action.

This idolatry is instinct—it is the whisper in Eve’s subconscious that fueled her desire to eat the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, it is the unadulterated anger that provoked the psalmist to wish for his enemies’ children to be dashed against the rocks, and it is the deep yearning we share to delineate and control the boundaries of our lives. And we do so in so many ways, drawing lines in the sand to define “us” and “them” so that “we” can prosper and “they” can look upon “us” with stupefaction.

Lest you think this a cynical line of thought, I’m merely suggesting (albeit quite broadly) a pragmatic approach toward the way we engage the inevitable golden calves in our midst. Institutions are inescapable, idolatry of them unavoidable, but we need not be ruled by the desire to make ours more permanent than the others.

In one thousand years, many of these institutions we hold so dearly will not exist—not in their current forms, at least; this kind of idolatry will continue to thrive as it always has; which leaves us with the grand predicament of how we are to carry on the important business of loving in the midst of so many golden calves.

It is one thing to raise the issue of the idolatry of institutions—it is another to offer a way out. I have none, except to make a battle cry against such a mindset that places things above people and institutional perpetuity above merciful, love-offering, and life-giving relationships.

We are not each other’s enemies—or even each other’s competition. And we’re not engaged in a cosmic battle against a little goateed man with a radiant-red hue, but we are playing out a sort of struggle against something that most often surfaces from within us. And this thing is powerful and subtle and ruinous, but love is stronger…so let’s get on with it.