A Family Tree Entwined with Slavery

My friend Kate was featured on NPR's "Race Card" project last week, talking about her family's history as slaveowners. Her grandmother upheld the "idea of the benevolent slave owner," telling Kate proudly that their family's slaves had been "trusted house servants," rather than plantation laborers. Kate eventually realized, however, that such pride is sorely misplaced. Reading Kate's story reminded me of last spring's "Movies That Matter" series here at St. James's, when we watched the documentary Traces of the Trade. Filmmaker Katrina Brown and her family members explored their Rhode Island ancestors' deep involvement in the slave trade. The film also highlighted how dependent all U.S. economic growth was on slavery, even for people who never owned or traded in enslaved human beings themselves. Much generational wealth, for northerners as well as southerners, was earned off the backs of African slaves. Katrina Brown and her family agonized over core questions that were also raised by Kate's story: To what extent ought we feel shame for our ancestors' involvement in injustice? Do we have a responsibility to attend to the wounds that remain because of what our ancestors did or did not do? And how can we even begin to do so?

Considering such questions helps me make sense of a biblical notion that I normally find hard to swallow. In the Exodus account of the Ten Commandments, and elsewhere in the Old Testament, God tells the people, "I the Lord your God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children to the third and the fourth generation." The notion that children should be punished for their parents' sin seems awfully unfair. But when we look at slavery's legacy in this country—at racially charged violence; economic and health statistics showing continued disparity between white Americans and African Americans; at the disparate effects of having ancestors who were slaves vs. ancestors who made money, in one way or another, off the slave trade—the "sins of the fathers" make more sense. Today's children continue to pay dearly for the sin of slavery.

Many of the online commenters responding to Kate's story, for good or ill, said that it is foolish to agonize over what one's ancestors did or did not do. "It has nothing to do with you," they said. "Get over it." Such a response ignores the weight and role of history, of course. What happened long ago, in our own families and in the world, has everything to do with us. But such observations are also correct in one way: Wallowing in shame for the bad things our ancestors did (or patting ourselves on the back for the good things they did) doesn't serve much purpose. Perhaps a more effective response to the sins (and accomplishments) of our fathers and mothers is found in another scripture verse, this time from the New Testament, Luke 14:26: Now great crowds accompanied him, and he turned and said to them, “If anyone comes to me and does not hate his own father and mother and wife and children and brothers and sisters, yes, and even his own life, he cannot be my disciple."

So instead of feeling shame or pride in our family's deeds, we should....hate them?

Jesus engages in some hyperbole to make a point about where our identity and allegiance ultimately lie. Our families influence us deeply in many ways, but if we define ourselves primarily or only in terms of our families' past and present, failings and triumphs, quirks and habits, we're missing out on the more abundant life that comes through Jesus. God in Jesus Christ invites us to define ourselves as members of God's family, to identify with all of God's people. God invites us to love others as devotedly and sacrificially as we love those in our own families, by working for justice, equality, and opportunity for all.

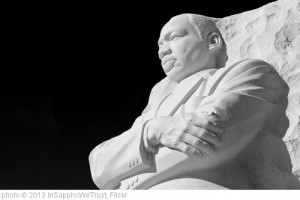

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Martin Luther King, Jr., Letter from Birmingham, Alabama jail, April 16, 1963

Ellen Painter Dollar is a professional writer and member of St. James’s Episcopal Church. She blogs for St. James’s every Monday, offering reflections on current events, family life, and parish life.