What It Means to Belong to a Church

In January 1999, Daniel and I drove north in an ice storm, leaving our home in Washington, D.C., for a newly rented apartment in West Hartford. At one point, the driver who had all our stuff in his moving van pulled over to sleep in his cab overnight, rather than continue crawling along the icy highways with terrible visibility. Our house plants, which the driver had agreed to take in the van even though it was against the rules, didn't survive the night of sub-freezing temperatures; they were a slimy mess upon arrival in Connecticut.

That my plants would thrive in our new home was one of several expectations that didn't survive our move. I knew, of course, that our new life would be different. After nearly 10 years of city living, we'd be settling down in a suburb—my hometown, no less, with my parents only a mile or so away. I would be telecommuting from home part-time instead of working full-time in an office. We hoped to start a family, and Leah was born before the year was out. I knew that finding a new church would be tough, particularly given how central our D.C. church had been in our lives; our quirky coffee-house church was where Daniel and I met, and where we also met our closest friends, including several other young couples with whom we regularly shared dinners marked by long, heartfelt conversations about God, culture, and relationships. I knew our D.C. friends were irreplaceable; we remain close with those friends today despite years and miles of separation. But I still expected that with patience and effort, we would find a new church and make friends with new couples, with whom we would share meals and conversation, swap recipes and child care, help each other paint a baby's bedroom or repair a leaky roof—just as we had in D.C. I believed that we would find a place where we belonged as clearly and completely as we belonged to our D.C. church.

At first, the struggle to find a new church was so strange and hard that it was funny. I wrote long emails to our D.C. friends describing awkward Sunday visits to just about every Protestant congregation in a five-mile radius of our West Hartford Center apartment. One Sunday, for example, we visited a Hartford congregation known for its social activism, family friendliness, and healthy bottom line. A kind—and ultimately mortified—usher tried to seat us three times. Three times, pew occupants apologetically but firmly shooed us away, explaining that these seats were saved. All we remember from the sermon is that the pastor kept talking about the alarm system he had installed in his West End home as if he'd moved into a gritty crime-riddled urban neighborhood. We had just moved from a city that was known not too many years ago as the "murder capital of the U.S.," where many church friends who chose to live in troubled urban neighborhoods would never dream of spending money on a security system. By the end of the service when, following communion, a woman and her grown daughter sitting in front of us giggled throughout the singing of "Let us break bread together," we knew this church wasn't the place for us.

But when the assistant minister at another church invited us to dinner at her house with some other young couples, I figured our search was over. Finally, we would begin building the friendships that would sustain us with fellowship and deep conversation, friendships like we had in D.C. But while the other couples at dinner were all very nice, and one was expecting a little girl around the time that our daughter was also due, it was obvious by the time dinner was over that these would not be "our people." There was plenty of polite conversation but no spark of shared interests or challenging questions. I began to understand that we might never find the kind of community we had in D.C., we might never help build an intimate community of peers like the one we left behind. I began to wonder if we would ever feel like we belonged to a church community the way we had belonged to that one.

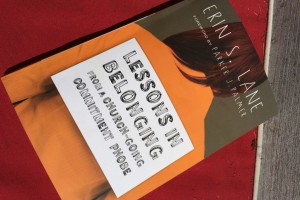

In her excellent memoir, Lessons in Belonging From a Church-Going Commitment Phobe, Erin S. Lane explores what it really means to belong, as she examines her own struggle to commit to a church in Durham, N.C. Lane discovers that belonging isn't something that happens to us, that we luck into or are guaranteed to find if we just keep looking hard enough. Belonging, rather, is something we do. It's less about being received by others than about showing up. Lane writes,

In her excellent memoir, Lessons in Belonging From a Church-Going Commitment Phobe, Erin S. Lane explores what it really means to belong, as she examines her own struggle to commit to a church in Durham, N.C. Lane discovers that belonging isn't something that happens to us, that we luck into or are guaranteed to find if we just keep looking hard enough. Belonging, rather, is something we do. It's less about being received by others than about showing up. Lane writes,

This is how belonging happens. Not by waiting for permission or holding out for perfect conditions. Not by cherry-picking people just like us or nitpicking people who don’t get us. Belonging happens when we choose to give ourselves away, saying, ‘Take. Eat. If you’ll have me, I belong to you.’…I’d had it wrong all along. Belonging didn’t chiefly depend on whether a community accepted me but whether I was able to offer myself to them.

Daniel's and my experience in our D.C. church was an authentic belonging, but it was one that we stumbled into. We were lucky. We both, independently of one another, walked into a community at a point when it was growing, when nearly every week brought new faces—many of them young, white, single Jesus-loving nerds just like us. While the church required a lot of us—we were expected to give generously of our time, commitment, and money—we didn't have to work very hard to be accepted in a place where most people looked and talked like us.

After a few months of "church shopping" in Connecticut, I realized that belonging to a church here was going to be a different thing altogether. Belonging here was going to require making the commitment first—saying, "If you'll have me, I belong to you"—and then going back week after week, month after month, year after year until the belonging felt like something real.

Going back week after week, year after year hasn't always been easy. I've been tempted to quit altogether. I could ascribe my reticence to the fact that no church here could measure up to my church in D.C., but I would be skirting the truth. The truth is, I sometimes wanted to quit that church too. I got fed up with the down sides of being in such a small community (we had about 25 members and a worshipping congregation of about 50). Nothing there happened without everyone being involved and giving significant time. I used to daydream about opening a church bulletin and reading about a variety of activities going on in the weeks to come, some of which were happening even though I had absolutely nothing to do with them! Then we moved to Connecticut and began attending churches where such bulletins are actual weekly occurrences. And of course I found other things to be frustrated with—for example, my children's vocal lack of enthusiasm for church (remedied, finally, when they joined the St. James's choir) or the New England-ish discomfort with saying the name "Jesus" with too much enthusiasm, lest we be mistaken for Bible thumpers.

I think the occasional desire to leave church behind, for good, is a necessary side effect of commitment, a sign that the commitment demands something of us. Bouts of anger and frustration are as unavoidable in a church commitment as they are in a marriage. In Lessons in Belonging, Lane believes that disillusionment with church is a necessary step in commitment.Letting go of our illusions of how a church should be—our literal "disillusionment"—is necessary for us to commit to a local church community as it is, rather than as we wish it would be. Throughout the book, Lane grapples with whether or not to join the church she's been attending most regularly in Durham, given that there are things she doesn't like. She dislikes the church's stance on women's roles and would prefer a service with the Eucharist, rather than a 25-minute sermon, at its center. Belonging, Lane writes, is about "enduring community when it's awkward, when small talk suffocates and the preacher gives bad sermons and the suffering of others is intrusive. It's about choosing to trust people, not because they've earned it but because you want it."

Lane speculates that the reason so many in her "millennial" generation identify as "nones" (those without any religious affiliation) isn't that they reject religious faith out of hand. Rather, she argues, having grown up in a time when divorce was commonplace and become adults in an uncertain economy, millennials understand just how much is required of us when we make a serious commitment, whether to a person, a job, or a community. It's not that they don't take commitments seriously, it's that they take commitments very seriously, and therefore don't commit lightly. Lane understands this, but she also sees the potential danger in looking at church—at the commitment required, at all the imperfections and frustrations that come with community life—and deciding that she can live without it. Driving home from a Good Friday service, Lane's mom wondered aloud "what our modern-day 'crucify hims' would sound like. What insults do we hurl at the nail-pierced feet of Jesus?" Lane goes on, "I try to think of some really gruesome ones, ones that would make most church folks blush, but when I finally settle on mine, it doesn't sound menacing at all. Still, I know it probably would have crushed him as heavy as those thorns. 'I don't need your church, Lord. I'm all good.'"

In the 16 years since we moved to West Hartford, I've had many moments of wanting to say to God, "I don't need your church. I'm all good." How much more pleasant it would be to enjoy leisurely Sunday mornings with a second cup of coffee, instead of the frenetic attempts to get everyone off to choir rehearsal by 8:30 that inevitably leave us all grumpy. I've got plenty of stresses and frustrations in my life without worrying whether the church budget will balance, or volunteering for a church project that isn't organized the way I would organize it.

But as hard as church membership can be, I feel as Erin Lane does, when she says, "there’s one commitment I won’t give up: the local church. The church is a package deal with belief in Christ; we are an unavoidable trinity of belonging—me, you and God. Members of one another rather than an institution, Christians are meant to regularly gather and practice our belonging as civil, compassionate and cross-bearing citizens of the world.”

When we moved from D.C. to Connecticut, we hoped to find a new community that would look a lot like the one we left behind. We never did. But we found what we needed most, which is a place where we belong. We learned that belonging isn't about shopping around to find a group of people just like us, or a place where we can check off all our requirements for an ideal community. Belonging is mostly about showing up, becoming disillusioned, and staying anyway.