Muslims in the Cathedral

Last Friday, the Washington National Cathedral, together with their director for liturgy, the South African Ambassador Ebrahim Rasool, Masjid Muhammad of The Nation’s Mosque, and representatives from the All Dulles Area Muslim Society, Council on American-Islamic Relations, Islamic Society of North America, Muslim Public Affairs Council, organized a prayer service for Muslims. For a press release that preceded the event, click here.

Their goal? To show hospitality and demonstrate “an appreciation of one another’s prayer traditions,” and make a “powerful symbolic gesture toward a deeper relationship between the two Abrahamic traditions.” This according to the aforementioned press release.

The Washington Post interviewed Ebrahim Rasool, a Muslim scholar and South Africa’s ambassador to the United States. Ebrahim said, “We come to this cathedral with sensitivity and humility but keenly aware that it is not a time for platitudes, because mischief is threatening the world,” Rasool said. “The challenge for us today is to reconstitute a middle ground of good people . . . whose very existence threatens extremism.”

During the prayer service, a whiff of extremism emerged as someone who had sneaked into the event stood up and told those gathered to “leave our churches alone!” She had driven from Tennessee solely for this purpose, this according to another Washington Post article. Hers was not the only complaint or critique, and to be clear, not every complaint or critique was extremist—many of the ones I saw were thoughtful and perfectly reasonable concerns. One of which called into question the ongoing identity crisis the church seems to be facing, a crisis that many fear will cause a watering down of our traditions and beliefs. As the National Cathedral holds a prominent place in the church and the country, it is no surprise that its actions are felt by people everywhere.

The National Cathedral serves as the cathedral for the Episcopal Diocese of Washington; it also houses the Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church’s chair (called a cathedra, from which the word “cathedral” comes). Furthermore, the actual cornerstone of the massive structure has inscribed upon it, “The Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us” (John 1:14).

There is no denying its role as a space for Christian worship.

And yet the explicitly stated mission of the National Cathedral, according to their website, is to be a “spiritual home for the nation.” Their vision is that they “will be a catalyst for spiritual harmony in our nation, renewal in the churches, reconciliation among faiths, and compassion in our world.”

In my opinion, the prayer service in question fits within that mission and vision. However, the prospect of non-Christian faith groups holding corporate prayer/worship in a space consecrated for Christian worship—especially one so prominent that is home to the presiding bishop’s cathedra—is one worth discussing. And maybe the National Cathedral needs to clarify its mission and vision; perhaps that is what they are doing by hosting this prayer service. And if the National Cathedral is doing this work, maybe—as the members of the churches in which it hopes to spawn renewal—we have some serious work to do.

The first bit of which is the question at hand: should groups with different theologies be allowed to use these spaces (in cathedrals or local churches)? If not, where do we draw our lines around what is theologically acceptable?

My field education site from seminary rents space to a mostly Latino Pentecostal church on Sunday afternoons. I overheard much of the preaching, and I can tell you that there are vast theological differences. Do we want to be so limiting to say that the only approved worship for these spaces is Episcopal? Do we want to leave it to the discretion of the rectors and deans, as it currently is (to my knowledge)?

In a perfect world, Interfaith houses of worship would be filled with people of all different traditions, dedicated to engaging the other in their Muslim, Christian, Jewish, Buddist, Sikh…etc. neighbor. We do not live in this kind of world. The Muslim Coalition of Connecticut offered free admission to an event called the Taste of Ramadan. It included guest speakers, table conversation, a delicious meal, and yes, prayer. While the event occurred in a neutral space—West Hartford Town Hall—the work of organizing, cooking, cleaning, and facilitating fell on the shoulders of this generous local group of Muslims.

The event had nothing to do with conversion, nor was there any watering down of my tradition or theirs or of anyone gathered. It was a night of sharing, learning, praying, hoping, and dreaming. And it happened because of a tremendous effort of generosity and hospitality.

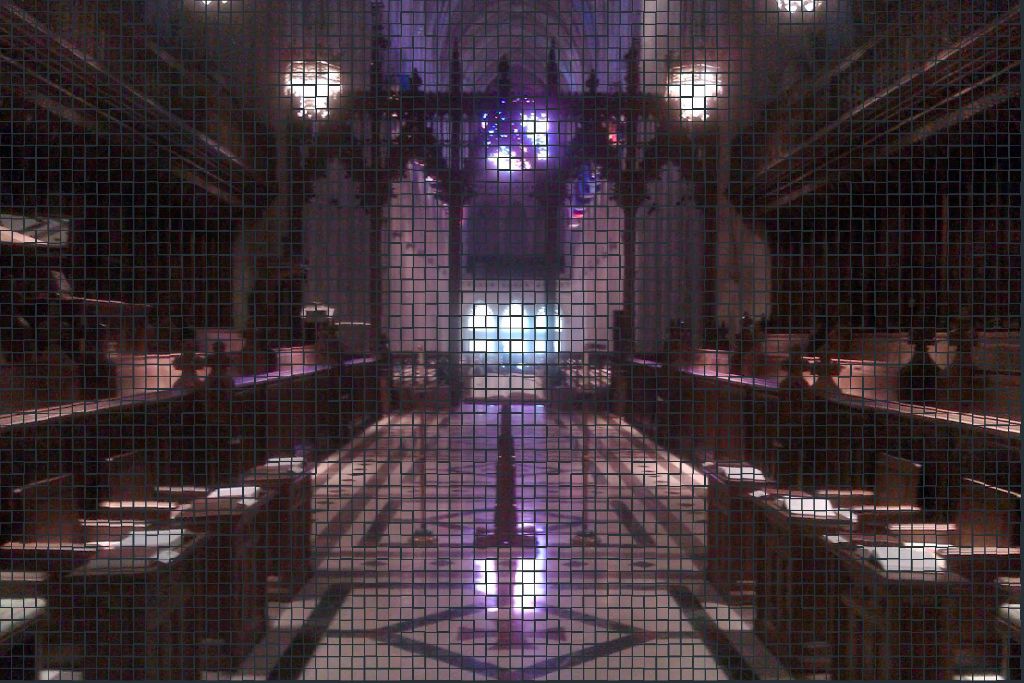

The prayer service at the National Cathedral was quite a bit different, yet it occurred because of the same kind of generosity and hospitality. It took the hosts to determine what they had to offer—in this case a beautiful sacred space with a particular purpose that could serve the needs of a community that is day after day turned into “the other” or “the stranger” because of hate, ignorance, or a lack of desire to engage them.

While it isn’t enough to say, “Jesus told us to welcome the stranger,” in order to rubber stamp every whim, it is also not enough to say that we (the church) need to find a way out of our identity crisis—especially if it happens premature to any real growth or deepening. I get that some are worried that we’ll lose the richness of our tradition if we crack ourselves open too much in the name of tolerance or political correctness; this is a very real fear for a lot of very good people, but we cannot allow that fear to prevent us from opportunities like these that (ideally) cause us to consider in a new way what it means to be a disciple of Jesus while engaging God's mission of reconciliation.

If we are to (and want to) cultivate a more static and unified identity as the Episcopal Church, we’re all going to have to make some sacrifices. Some of us might have to think liberally about how we use our space. Others of us will likely need to be more rigorous in the way we cultivate and speak to our beliefs (it is okay to believe in the Incarnation, virgin birth, and bodily resurrection…though I won’t force you into it).

Bottomline: we will all need to be patient with the hot messes that we are.

God help us all.

Curtis Farr is the assistant rector of St. James's. He is a hot mess.